Seven years ago, I contracted a temporary life-threatening illness called Guillain-Barré Syndrome, a rare autoimmune neurological condition that had the potential to paralyze me to death.

At the time, I had just left my start-up and embarked on a year-long personal sabbatical, which took me traveling along back roads, across jungles, and up mountains throughout Central America for several months. One day a couple of months into my journey, I found myself on a bus crossing the border from Panama into Costa Rica when I reached into a bag of nuts for a little snack and discovered that my hand wasn’t working. I could no longer feel my fingers and I couldn’t curl them enough to grasp anything. Needless to say, I had no idea what was going on—and I was terrified.

When we got to San Jose that night, I tried to put my growing worries out of my mind and get some sleep. Maybe I was just exhausted, I thought. It’ll be better in the morning.

But it wasn’t better in the morning. It was worse. When I woke up, I couldn’t feel my hands, my feet, or my face. Trying not to panic, I immediately booked a flight home to Toronto, abruptly ending my long-awaited year of travel. I got off the plane and went straight to the hospital, where I was quickly diagnosed with Guillain-Barré, a rare autoimmune neurological disorder in which the body’s immune system goes haywire and attacks its nerve cells. The doctor said, “This thing can progress fully in just four weeks—in that time, you could be fully paralyzed.” If the disease continued on its current course, my lungs would shut down, I’d stop being able to breathe, and I’d die from organ failure.

This, I learned, is the cruel fate that awaits upwards of 20 percent of people who contract this disease (thankfully, seven years later the mortality rate is now somewhere between 5-7.5%). The doctors told me at this stage there was nothing they could do to prevent it. We’d just have to “wait and see” what happened over the next month. And I’m sure you can imagine what kind of waiting game that was. Let’s give it four weeks, and hopefully, you won’t die.

I was a wreck. I couldn’t be alone. My brother was gracious enough to let me crash in his bed while he slept on the couch. I remember so many sleepless nights in his apartment, staring at the ceiling absolutely terrified that I was going to die. I had dreams of dying, feeling completely helpless as my organs shut down one by one and I lost all control of my body.

But I turned out to be one of the lucky ones. Roughly twelve days into the illness, a close friend pulled me out of bed and organized a surprise birthday dinner for me. The room was full of my closest friends. The tears started flowing and wouldn’t stop for at least an hour. Was this the last meal I should share with my closest people? I was completely and utterly blasted with love. A couple of days later, the paralysis began to plateau. It was a miracle for me. Over the next year, I slowly began to regain my muscle function and sensation in my limbs. At the one-year mark, I regained 95% of my former capacities, and in the three years that followed, the remaining 5% returned.

I may not ever know what caused my body to begin to attack itself suddenly. In two-thirds of cases, the onset of the illness is preceded by a viral or bacterial infection—so there’s a good chance that I was exposed to something in the food or water in Central America that set off my system. It didn’t really matter. What mattered at the time was that I was alive and that I had a challenging year ahead of physical recovery and rebuilding my life. I wasn’t working, I couldn’t travel, and I was living in my parent’s basement, withdrawing from normal life as my symptoms slowly improved. The inflammation and neurological impacts of the disease had left me with persistent fatigue and brain fog, which meant that I couldn’t work. I couldn’t make money. I couldn’t enjoy much time with friends or go about my life as normal.

I ended that year grateful to be alive and functioning but with a major case of post-traumatic stress disorder that would continue to impact my life for years to come. Even after I had largely recovered, I couldn’t shake the deep inner conviction that I was dying. I was convinced there was something wrong with me. At any moment, my body could turn against me. A headache or muscle ache took on an entirely new meaning. This intense fear around my health and physical well-being persisted for years.

For six years, I went to therapy regularly to work on my fears about this illness, dying, and the loss of my physical faculties. But I was never able to totally crack it until I saw Wesly Feuquay, a co-founder of the Rapid Rewire Method, who helped me to unravel it all in one single session. Our first session together gave me exactly what I’d been looking for (but hadn’t found) in years of therapy.

The key? A simple and subtle shift of perception. All these years, I’d been relating to the emotions around my experience with Guillain-Barre as fear—intense, uncontrollable fear. I was very familiar with fear and had spent many years feeling my fear, often in men’s group settings. Then Wesly came along and said: What would happen if you related to this as insecurity?

That reframe somehow changed everything. Before, I felt shaky and scared about my physical health. I was terrified that my physical body was vulnerable, that it wasn’t as healthy or strong as it should be—which meant that I would soon die a horrible, painful death from a terminal illness. But once we labeled this emotion as insecurity rather than fear, I was finally able to look it in the eye and explore it for the first time.

In one session, I was able to acknowledge the truth of the situation, which was that my body was not perfect. It was vulnerable and it would struggle from time to time, but it was certainly good enough for me to live a long, healthy life. I was also able to acknowledge the truth that I felt insecure about my health. All of a sudden, all that fear—the intense electrical charge of emotion that would course through my body—just dissipated. For the entire following year, I only experienced a few irrational fears around my physical health (which is a massive improvement!).

So what is insecurity, really? And why did it help to relate to my emotions as insecurity instead of fear? Insecurity is being vulnerable, uncertain, lacking protection, and open to threat or loss. From my experience participating in and facilitating men’s groups, we spend a lot of time exploring and feeling fear, sadness, and anger but almost no time exploring insecurity. It got me thinking, Wow, that was sneaky. The insecurity was hiding in plain sight. I had an identity of not being an insecure person, so I simply didn’t entertain that as a possibility. But all humans experience the full spectrum of emotions, I was only feeling some of those emotions. Once I was able to acknowledge that it was true for me, I was able to feel it and ultimately process it.

Maybe it wasn’t just my body that I was insecure about. Was I secretly feeling a sense of insecurity in other areas of my life? Sure enough, once I started digging, I found other places where insecurity was present. When I’d give a talk, I would typically feel quite insecure about my ability to show up and perform at the level that was needed for the talk to go well. I noticed some insecurity present when I was around certain people. Sometimes I felt insecure about climate change, nuclear warfare, and the general state of the world.

As many great teachers across wisdom traditions (especially Buddhism) have noted, this state of not being on solid ground is actually the basic nature of life. We’re never really standing on solid ground; any sense of certainty or security we have is just an illusion, a trick of the mind. No matter how secure we think we are, no matter how much money or support we might have, the rug could still get pulled out from under us at any moment. Living with this kind of insecurity and uncertainty, Pema Chodron writes, is the “training ground of the spiritual warrior.” She tells a great story about a woman being chased by tigers who finds herself hanging off the edge of a cliff, trying to escape them, and then looking down to see that there are also tigers below her. She looks next to her and sees a beautiful patch of wild strawberries, decides to eat one, and fully enjoys it. That’s life, she says: “Tigers above, tigers below. This is actually the predicament that we are always in, in terms of our birth and death. Each moment is just what it is. It might be the only moment of our life; it might be the only strawberry we’ll ever eat. We could get depressed about it, or we could finally appreciate it and delight in the preciousness of every single moment of our life.”

If we can stop trying to eliminate our feelings of insecurity, we can just relax and enjoy the strawberries. We can live our lives fully, even if we don’t know whether we’ll ever regain full control of our fingers and toes. Even if we don’t know if we’ll get sick again. Even if we don’t know if we’ll ace the meeting, or ever sell our company, or get to financial freedom. Is it possible to enjoy our lives anyway?

Last month, I was lucky or unlucky (depending on how you look at it) to have the opportunity to put this newfound wisdom into practice in my life. To embody what I had come to know on the deepest level.

After a busy month and a half of going full-throttle with some exciting new business opportunities and a full roster of clients, I started re-experiencing some of my Guillain-Barré symptoms for the first time in nearly four years. And it blindsided me because I thought I was fully healed (physically and psychologically). Initially, I went straight into the PTSD fear response. I was going to die, there was no way around it, just as my business and my family are growing and my life is flourishing. Of course. The tigers are catching up to me. But I was quickly able to step back and reorient, shifting my center of awareness back into my rational brain. Yeah, you know, I said to myself, I’ve just been a little stressed with everything going on this month. That must be kicking up some old stuff in my immune system. It’s all good, I just need to rest. I remembered my session with Wesly and thought, It’s just insecurity. That’s OK.

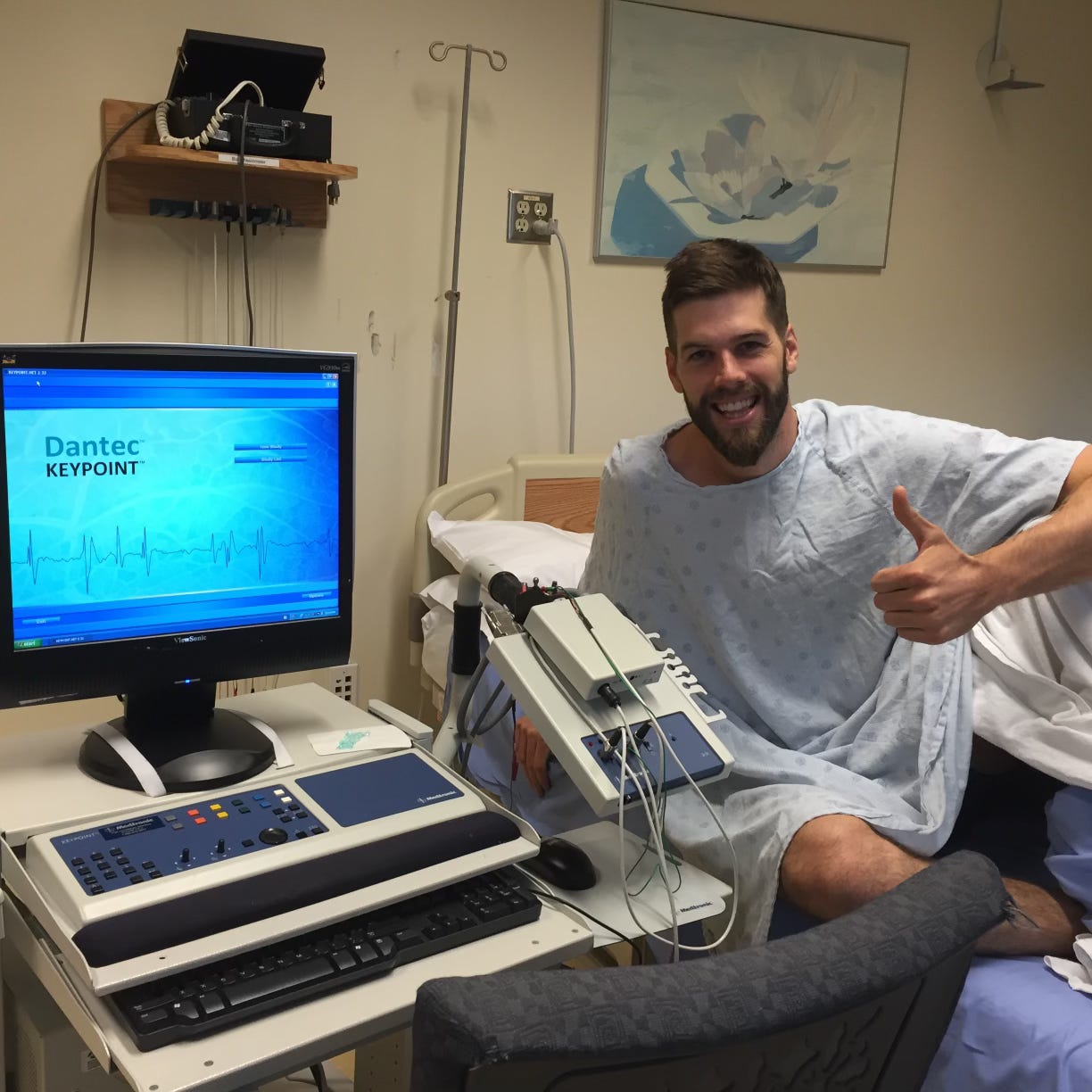

Then I woke up two days later and it was worse, and I fell into a state of terror and panic. I was convinced that I was relapsing (7% of cases do) and that it was the end. It’s a month later now, and I’m not going to lie, it’s been a hard month. I’ve really had to live my practice, use all my tools, and lean on everything I’ve learned through my healing journey and personal work over the years. I went to the doctor, and he did some tests on me and said that from a neurological standpoint, I was OK. Then I went to my therapist (who is well-versed in the workings of the nervous system), and he agreed that it was probably just a stress response. I overstressed myself by saying “yes” to so many opportunities at once and working so hard, and it put me above my threshold. One I hadn’t crossed since my days of intense work at Founders Pledge.

It’s been incredibly humbling because I thought I had nipped this thing in the bud—not only the illness but also the fear and the trauma response. As of today, I can safely say that neither of those things has turned out to be true. And yet, something’s changed. I have more moments of coming back to myself—moments of being relaxed and feeling OK. Moments of forgetting the terrifying predicament I was in. Moments of accepting the impermanence of this vessel I inhabit. Somehow, I have been able to ride the waves of insecurity with some level of acceptance. It has been challenging and scary, I wouldn’t wish it on anyone. But… I’m also alright. I could still go outside for a walk in the fresh air. I could still enjoy dinner with my wife. I was scared, and I had moments of relaxing into the insecurity, just being with the situation, letting it be OK.

Alan Watts writes in The Wisdom of Insecurity: “To remain stable is to refrain from trying to separate yourself from a pain because you know that you cannot. Running away from fear is fear, fighting pain is pain, trying to be brave is being scared.”

When fear strikes, instead of running away from it, what if we can relate to it as a response to life’s insecurity? What might happen if you were able to lean into it?

I want to encourage you to venture into the land of insecurity. Particularly if you identify as someone who has a high need for stability and security in your life. By cultivating a greater awareness here and simply being able to see insecurity for what it is, knowing that it’s a basic aspect of life, maybe you can relax a little. And if you’re anything like me, just knowing this might help you resolve some pretty major internal challenges.

I love these posts. There is something about Matt's writing that just captivates me. Keep it up man!

Hunter, WOW. I knew you struggled with your health back in the day, but I did not know these details. Such a harrowing journey. The scene with you and your friends thinking it was your last meal with them was chilling. I'm so damn grateful you were OK then and are OK now. Thanks for sharing this. The writing just keeps getting better. Excited for more. Love you.